|

A NORFOLK FARM – LOOKING BACK

In a broadland village, about sixty years ago, I first came to know Whin Farm, lying about a hundred yards from my home, where on calm autumn evenings the roar of breakers tumbling on wide sands could sometimes be heard. The lay-out of the farm is much the same as it was then, but the farm house, with its old-fashioned kitchen and open fireplace, has been replaced by a comparatively modern building.

|

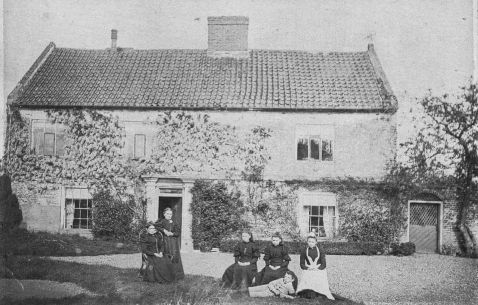

The modern building, as it was in 1915 when occupied by the

Disney family

|

Often on a cold winter morning, sleepy and shivering, I have been in the old kitchen when I went to fetch milk, and stood by the wood fire burning on a grateless hearth, peering up through the smoky chimney at stars and in the clear sky. Skim milk was a ha-penny a pint and the cream had been taken from it by hand with a “skimmer”. Such milk, boiled and poured over whole-meal, home-baked, bread, made from meal, stoneground in a local windmill, provided breakfast for half a dozen hungry children in my family six mornings out of seven.

Sunday brought a special breakfast of sausage rolls, or an occasional egg. Baker’s white bread we looked on as a rare treat, and we eyed with envy during the school dinner hour children who always had baker’s bread with their cheese. The day came when into the dairy at the farm came a separator, looking to us like a miniature, stationary traction engine. Consternation reigned amongst the milk-fetchers when they saw the milk from it. It looked bluish and we all said oil from the machine had got into it.

The farm fields which formed a fairly compact, rectangular block were flat and fertile, so free from stones that it was hard to find one to throw at a bird or animal. Their names are still as familiar to me as those of the days of the week: the Barn Piece, the Long Piece, the Top Piece, the Footpath Piece, the Garden Piece, the Entry Piece, the Eighteenacres, the Thirty-two acres, Brickley (with pits and ruins of brick-burning “calamps”) the Back O’Cover Pieces, etc. Each was explored by me with the zest of a young Linvingstone. The farm was rigidly run on a Four Course System – wheat, roots, barley or oats, hay – made famous by Coke of Holkam. Old Billy was once heard to reckon the date of a past local event by counting back in four year periods. “It happened when the Thatter–tu Eakers wuz a tarnaps!” said he, and that was conclusive.

As a small boy I was thrilled by the vivid Bible stories I heard, - particularly with those from the Old Testament – and pictured their heroes having lived in the only surroundings I knew. So David sent out to slay Goliath from near a big ash in the Eighteen Acres, Jonathan shot his arrows while David watched, hidden in the overgrown hedges in the Garden Piece, while Jacob slept with his head on a stone in the Footpath Piece and so on. For some reason the site of the Garden of Eden shifted about on the farm. Still its site has always apparently been difficult to locate!

Great was the excitement when the old farmhouse was pulled down and the walls of the new one rose. Middle-aged John who had never been to school and had worked on Whin Farm nearly all his life, shared in the excitement. He knew the fields and hedges on it like the lines on the palm of his hand. His first master had been an autocrat. Once when young John displeased him, he gave a boy a kick in his behind and sent him home. Whereupon his father, who had many children, promptly sent him back to the farmhouse where he “lived in”. One night there, in bed in an attic, he hard a large rat “plump” on the bare floor. In the morning when he went to put on his grey worsted stockings one was missing. Despite careful search he could not find it. When the attic was being pulled down, John, who by this time was a yardman, was watching a workman stripping off the false ceiling made of reeds and plaster between the rafters. Suddenly the man came on a much crumpled and discoloured old grey stocking. Throwing it down onto the yard, he shouted, “Hare y’are John! Hare’s the stocken you lorst yares ago!” The rat had taken it up into the roof as nesting material.

John’s father and grandfather had worked most of their lives on Whin Farm. It was said that his grandfather, Robert, would hold a prayer meetings in the stable on dark winter mornings while the horses were eating their “bait” before going into the fields to work.

Automatic bird scarers have almost superseded “crow-keepers” and “mawkins” [?], but when John was young, small boys were usually set to frighten rooks off newly-drilled corn. “Clappers” and a loud yell of “KarWoo!” would scatter a flock of birds, but not for long. John was once planted in a bullock “bing” in the middle of a field and armed with a rusty muzzle-loading gun. He was provided with plenty of powder but no shot. This did not suit him long. Collecting small stones he used them as shot! His guardian angel must have seen to it that the old barrel did not burst. John as a man became an excellent short with “an eye like a hawk”. He used to tell us how on a wild February day he had seen a few wild geese light in a small pond in the middle of the Thirty-two Acres, and how, creeping over the snow, he bagged one with his nine-bore gun.

Bullocks occasionally used to run a muck [sic] when they were taken out of the yard after months of confinement to be driven to the nearest railway stations on the way to market. All ordinary efforts to round them up sometimes failed and children were terrified when they knew that a “mad bullock” was at large. One such animal was shot by John who waited in a gap in a hedge till the charging beast came within range.

Norfolk people have a saying that no-one has ever seen a dead donkey, but when the farm “chicken” got too old to work, and suffered from “snatchews,” [?] – a complaint which made its feet painful so that it lifted them from the ground very quickly after touching it – John shot the animal. It was buried in the disused sawpit.

Years ago every big farm had one, and with its thick uprights and cross means it looked like a small woodhenge. It was fascinating for children to watch a big tree being sawn into planks, with one man standing on the framework above the pit pulling the long saw upwards, and his mate in the pit pulling the saw downwards.

A saw pit not in use was a grand playground for children; there were beams to climb and swing on and a fall caused little hurt owing to the sawdust.

It is said that childhood memories remain clear because impressions made on a child’s mind are like writing on a clean page. Be that as it may, my memories of Whin Farm are as fresh as ever, though it is over fifty years since I last wandered happily around it.

“Young Doss”

Edward W Platten

First published October 2013

©SMalleson2022

Below is a picture

of the old Whinmere farm house. The farm has been in the

ownership of the Micklethwaite Mills family since around 1750.

One of them was referred to in Oliver Ready's book as the 'Raverand'.

Pictured in this photograph are members of the Slipper family

who farmed at Whinmere between 1824 and 1904.

|